The ‘10-Hectare-for-254-Hectare Mistake’ That Sparked the Mother of All Defamation Wars Between Dele Farotimi and Chief Afe Babalola

The ‘10-Hectare-for-254-Hectare Mistake’ That Sparked the Mother of All Defamation Wars Between Dele Farotimi and Chief Afe Babalola [ Ope Banwo, Founder of Naija Lives Matter is an Attorney and public Affais Commentator]

At the center of the escalating legal battle between Chief Afe Babalola and Dele Farotimi lies a perplexing issue that raises earnest questions about judicial integrity: how did the Nigerian Supreme Court—the nation’s final arbiter of justice—make an error as glaring as writing “10 hectares” instead of “254 hectares” in its judgment? This is not the type of mistake that can be brushed aside as a minor oversight. The implications are far-reaching, both for public trust in the judiciary and the massive financial stakes involved.

Did the Supreme Court Really Make a Genuine Mistake?

The claimed clerical error by the supreme court in its 2014 amended ruling originates from the Supreme Court’s 2013 judgment it gave in the case of Major Gbadamosi vs. Oba Akintoye (2013 LLJR-SC In this case, the supreme court had awarded 10 hectares to the Eletu family. However, nearly a year later, in 2014, the court revised its decision, after a motion was filed by Chief Afe Babalola’s Law Firm, under the so-called Slip Rule, and now claimed that the correct figure they meant to state should have been 254 hectares.

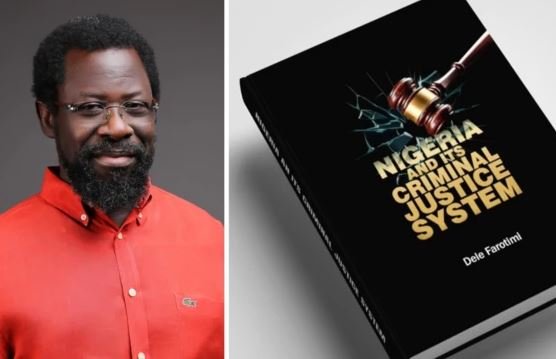

This bizarre turn of events has become one of the central grievances in Dele Farotimi’s critique of the judiciary, as expressed in his controversial book. And for good reason—it is difficult to understand how such a monumental “mistake” could occur in the first place.

I took the time to review the FULL 2013 judgment, found and reported here for anyone to read too : https://www.lawglobalhub.com/major-muritala-gbadamosi-rtd-ors-v-h-r-h-oba-tijani-adetunji-akinloye-ors-2013-lljr-sc/ and what I found was troubling. I noted during my reading of the judgement that The Supreme Court, in its 2013 ruling, referenced “10 hectares” several times—on Page 11, Page 16, and Page 17—as the portion of land due to the Eletu family after it had analyzed the different stages the original sale of 254 went from sale, to acquisition by Lagos state; to lawsuit by Ojomu family to void the acquisition; to judgement in favor of Ojomu family; to challenge by Eletu family; to compromise of the judgement and different compensations given by Lagos state to acquire back some of the land etc.

While the court acknowledged at the beginning of its judgment that 254 hectares was originally sold to the Eletu family in 1973, it can also be deduced from its judgment that the subsequent legal battles, government acquisitions, and settlements left only 10 hectares as the land remaining for the family. The court’s analysis in its judgment repeatedly emphasized this ‘10 hectares’, even converting it to 24.7 acres in one instance. This was not a one-off slip. The term “10 hectares” was consistently used in the judgment to describe the land awarded to the Eletu family. How, then, can it now be claimed that the justices meant to write “254 hectares” all along?

Yes, I read the judgement in full. The supreme court clearly stated in at least 3 different places that the portion now due to the Gbadamosi Eletu family is now 10 hectares (which it also described in words as 24.7 acres)

Here are 3 very specific references in the judgement where the supreme court was clear it meant to give judgement of ‘10 hectares’ to the Eletu family, not the ‘254 hectares’ it later claimed it intended after Chief Afe Babalola Law Firm has filed a motion asking it to reverse itself in 2014

1. Page 11 of the lawglobalhub.com report of the case: “Any negotiation embarked upon between the respondents and the Lagos State Government which led to the excision of some portions of the acquired land would be vested in the party whose interest was subsisting. And following the terms of agreement reached between the appellants and the Lagos State Government on 20th May 1996 which became the judgment of the Court in Suit No. M/779/93 (Exhibit C3), the Excision Notice of June 23, 1994, should vest the 10 hectares (approximately 24.17 acres) reclaimed land in Osapa Village in the appellants.” – JSC KUMAI BAYANG AKA’AHS PAGE 11 of the Report in the Supreme Court decision of 213

2. page 16 of same judgement report: “ “The settlement agreement reached between the appellants and the Lagos State Government reduced the entitlement of the appellants from 18.05 Hectares to 10 Hectares.” – PAGE 16 [JSC KUMAI BAYANG AKA’AHS]

3. Page 17 (last paragraph)- Again the supreme court referred to “10 Hectares” at the end of its analysis “The appellants are entitled to the statutory right of occupancy over 10 Hectares (which is approximately 24.l7acres) of the reclaimed land in Osapa Village which has been excised and assigned to them, a sketch plan of which was attached and marked ‘SCHEDULE 1’ to the terms of settlement dated 20th May, 1996andd made the judgment of the Court in Suit No. M/779/93” PAGE 17 (Per JSC KUMAI BAYANG AKA’AHS]

A Mistake That Doesn’t Add Up?

Mistakes happen, but this one stretches credulity. Writing “10 hectares” instead of “254 hectares” is not a simple clerical slip like transposing digits. The two numbers are vastly different in scale and significance. For context, 10 hectares is a fraction of the original land, while 254 hectares represents the entirety of what was sold in 1973.

Even more worrisome to me is the fact that the Slip Rule correction came eight months later, after the involvement of Chief Afe Babalola’s chambers. Why did it take so long for this “error” to be discovered and corrected? And why wasn’t it flagged by the affected parties or their lawyers immediately after the judgment was delivered? Why didn’t the other 4 lawyers in the case flag it and inform the judge reading the lead judgement of the error? Did the other supreme court judges who concurred in the ’10 hectare’ case not read the lead judgement before concurring

In my one thinking, and with profound respect to the justices of the supreme court who make this mistake, to claim of a slip in writing ‘10’ when you meant ‘01’; or claiming you wanted to write 100 when you wrote ‘10’ is easy to understand, but claiming a ‘clerical’ mistake for writing 10 when you meant ‘254’ is very strange to me.

A slip is when you missed a step while coming down 10 stairs, but you can’t jump 244 stairs and then claimed you ‘slipped’. That would be seen by any objective listener as not adding up to a slip

The original judgment left no ambiguity. The court analyzed the complex history of the land disputes, government acquisitions, and settlements in detail, and its conclusion was clear: 10 hectares was the portion remaining for the Eletu family. Without me accusing anyone of anything, lest I may be carted to jail in God knows where, the idea that all five justices of the supreme court, along with their clerks, missed this glaring “error” in multiple references in the lead judgement, is, frankly, hard to believe. Unless of course there are more facts of which I am not aware.

Was the Slip Rule Properly Applied?

The Supreme Court’s reliance on the Slip Rule to correct the alleged error adds another layer of controversy. For context, the Slip Rule is typically used to correct minor typographical errors or unintended omissions in judgments. However, revising a decision from 10 hectares to 254 hectares is no minor correction. It fundamentally alters the outcome of the case, with billions—if not trillions—of naira at stake.

This raises a critical question: was the Slip Rule abused in this case? The original judgment consistently referred to 10 hectares as the remaining portion of land, and there was no indication that the court intended to award 254 hectares. The basis for the revision appears flimsy at best, and deeply suspicious at worst.

Why This Does Not Pass The Smell Test In My Considered Opinion:

The timeline and circumstances of this case only add to the suspicion. The so-called “error” was corrected long after the original judgment, following the intervention of Chief Afe Babalola’s chambers. If you were on the losing end of this correction, would you not question the genuineness of the “clerical error” coming 8 months after the fact and after you have started trying to execute the judgement? And you don’t have to be officially in the case as an attorney or even a litigant to scratch your head at this about turn.

Also, the supreme court is supposed to be a final court of judgement and the court that ends all litigations. As Justice Amina of the Supreme Court forcefully reinforced in another case where it was asked to review its own judgement, and which incidentally involved the same Chief Afe Babalola’s chambers, it should not be an easy thing to ask it to reverse itself. To make sure the point sank home, JSC Amina Aguiy had fined Chief Afe Babalola, and his co-counsels the sum of N30Million for their audacity in asking the judge to reverse itself in the Bayelsa Election case.

Sure, minor clerical errors may be okay, but I doubt anyone thinking about it would agree that writing ’10 hectares’ 3 times in a judgment. instead of ‘254 hectares’ as later claimed, is a ‘simple clerical error’… an error that makes a difference of 100s of Billions of Naira (If not trillions).

The Stakes: More Than Just Land

The financial implications of this “mistake” are staggering. Prime Lekki land is among the most valuable real estate in Nigeria. 10 hectares might have been worth ₦500 million at the time, but 254 hectares would run into billions, possibly trillions. This is not the kind of mistake one can dismiss lightly.

For those on the losing end, it is only natural to feel aggrieved and suspect foul play. Even if no fraud occurred, the sequence of events and the extraordinary nature of the correction invite skepticism.

Dele Farotimi’s Allegations: Reasonable or Reckless?

Given the circumstances, is it truly unreasonable for someone like Dele Farotimi to suspect corruption? While he may not have direct evidence of collusion, the inconsistencies and unusual actions in this case provide ample grounds for suspicion.

This is not to say that Farotimi’s conclusions are necessarily correct. But criminalizing his allegations through defamation charges—rather than addressing them in a civil court—only serves to deepen the public’s distrust in the judiciary.

A Wake-Up Call for Reform

This case is about more than just land or defamation. It exposes cracks in Nigeria’s judicial system that demand urgent attention. The Supreme Court’s role as the final arbiter of justice is meant to inspire confidence, not controversy. If such monumental “mistakes” can occur at the highest level, what hope is there for justice at the lower courts?

As this saga unfolds, one thing is clear: the judiciary’s credibility is on trial. Whether intentional or not, the “10-hectare-for-254-hectare mistake” has become a symbol of the challenges facing Nigeria’s legal system—and a reminder of the need for accountability and transparency.

whoah this blog is magnificent i love reading your posts. Keep up the great work! You know, lots of people are hunting around for this information, you can help them greatly.

This is the post that should have been made popular. It is sad that our media houses even failed to look at the judgment in contention. Its equally sad that lawyers wasted an inordinate amount of time on social media commenting on the issues without even looking at the original judgment. Its painful that the Supreme Court, the institution at the centre of this mess, has also not made any statement in relation to the case.

I don’t think the title of your article matches the content lol. Just kidding, mainly because I had some doubts after reading the article.

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me?

I want to thank you for your assistance and this post. It’s been great. http://www.hairstylesvip.com

I want to thank you for your assistance and this post. It’s been great. http://www.hairstylesvip.com

Thank you for writing this post. I like the subject too. http://www.hairstylesvip.com

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me.

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me.

Möchten Sie den Hintergrund Ihres Desktops mit wunderschönen Bildern verschönern? Dann ist die Website wallpapers4screen.com genau das Richtige für Sie. Auf dieser benutzerfreundlichen Plattform finden Sie eine riesige Auswahl an hochwertigen Hintergrundbildern für Ihren Desktop. Egal, ob Sie Natur, abstrakte Kunst, minimalistische Designs oder moderne Bilder bevorzugen – auf wallpapers4screen.com gibt es für jeden Geschmack das passende Wallpaper. Der Downloadprozess ist einfach: Wählen Sie einfach das gewünschte Bild aus, klicken Sie auf den Download-Button und speichern Sie es auf Ihrem Computer. Nach dem Herunterladen können Sie es als Hintergrundbild auf Ihrem Desktop festlegen. Die Website bietet eine Vielzahl von Kategorien, sodass Sie leicht das perfekte Bild für Ihre Bildschirmgestaltung finden können.

Your point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you.

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me?

Fantastic web site. Plenty of useful info here. I am sending it to a few friends ans also sharing in delicious. And of course, thanks in your effort!

Link exchange is nothing else but it is just placing the other person’s

blog link on your page at appropriate place and other person will also do similar in support of you.

my webpage … nordvpn coupons inspiresensation

I would like to thank you for the efforts you have put

in penning this website. I am hoping to view the same

high-grade content by you later on as well. In truth, your creative writing abilities

has encouraged me to get my own, personal site now 😉

Feel free to visit my web site: nordvpn coupons inspiresensation

I blog quite often and I truly thank you for your

content. This great article has really peaked my interest.

I will book mark your blog and keep checking for new information about once a week.

I subscribed to your RSS feed too.

Also visit my webpage :: nordvpn coupons inspiresensation

We are a group of volunteers and starting a new scheme in our community.

Your website offered us with valuable info to work on. You have done a formidable job and our entire community will be grateful to you.

my web-site … nordvpn coupons inspiresensation (http://tinyurl.com/2cc6rsmk)

Hello friends, its enormous paragraph on the topic of educationand fully explained,

keep it up all the time.

Feel free to visit my blog; nordvpn coupons inspiresensation

Your writing doesn’t just inform — it embraces, uplifts, and invites the reader to linger and reflect.

Nordvpn special coupon code 2025 350fairfax

You actually make it appear really easy with your presentation but I in finding this matter

to be actually one thing which I think I’d never understand.

It sort of feels too complicated and extremely vast for me.

I am looking ahead for your subsequent submit,

I’ll try to get the dangle of it!

This work has an almost meditative quality to it. Each sentence feels carefully considered, yet they flow so naturally that it feels effortless. The insights you’ve shared seem to carry the weight of experience, and there’s a gentleness to the way you present them, as though you are offering the reader a piece of wisdom that you’ve carefully cultivated over time.

Thanks for sharing. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good. https://accounts.binance.com/sl/register-person?ref=OMM3XK51

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me?

Thanks for sharing. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good.

I believe this is among the such a lot vital information for me. And i’m happy reading your article. However want to commentary on some common things, The web site taste is perfect, the articles is in reality excellent : D. Excellent task, cheers

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me.

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!

Thanks for sharing. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good. https://accounts.binance.com/lv/register?ref=B4EPR6J0

Fascinating blog! Is your theme custom made or did you download it from somewhere? A design like yours with a few simple adjustements would really make my blog stand out. Please let me know where you got your theme. Many thanks

Thank you for sharing this article with me. It helped me a lot and I love it. http://www.kayswell.com

I’m really enjoying the design and layout of your site.

It’s a very easy on the eyes which makes it much more enjoyable

for me to come here and visit more often. Did you hire out a designer to create

your theme? Excellent work!

my webpage … Eharmony special coupon code 2025

Thank you for your articles. http://www.kayswell.com They are very helpful to me. Can you help me with something?

You’ve the most impressive websites. http://www.ifashionstyles.com

This website is my breathing in, real excellent design and perfect content material.

I really appreciate your help http://www.ifashionstyles.com

If you want to grow your familiarity just keep visiting this site and be updated with the

hottest gossip posted here.

Look into my webpage :: vpn

Please provide me with more details on the topic http://www.ifashionstyles.com

Please tell me more about this. May I ask you a question? http://www.kayswell.com

Thank you for your articles. I find them very helpful. Could you help me with something? http://www.ifashionstyles.com

You helped me a lot by posting this article and I love what I’m learning. http://www.hairstylesvip.com

I enjoyed reading your piece and it provided me with a lot of value. http://www.ifashionstyles.com

Your articles are very helpful to me. May I request more information? http://www.kayswell.com

Good day! Would you mind if I share your blog with my zynga group? There’s a lot of people that I think would really appreciate your content. Please let me know. Cheers

I consider something really special in this website.

Thank you for sharing this article with me. It helped me a lot and I love it. http://www.kayswell.com

Thank you for your post. I really enjoyed reading it, especially because it addressed my issue. http://www.kayswell.com It helped me a lot and I hope it will also help others.

You’ve the most impressive websites. http://www.kayswell.com

Thank you for sharing this article with me. It helped me a lot and I love it. http://www.kayswell.com

I’d like to find out more? I’d love to find out more details. http://www.ifashionstyles.com

You’ve the most impressive websites. http://www.kayswell.com

I loved as much as you will receive carried out right here.

The sketch is tasteful, your authored material stylish.

nonetheless, you command get got an nervousness over that you wish be delivering the following.

unwell unquestionably come further formerly again since exactly the same nearly

very often inside case you shield this hike. https://tinyurl.com/2ah5u2sb gamefly

Your articles are extremely helpful to me. Please provide more information! http://www.kayswell.com

I enjoy you because of all of the work on this web page. Ellie really likes conducting research and it is obvious why. Most people notice all of the dynamic means you render vital tips via your website and even recommend participation from other people on that concern while our favorite child is being taught so much. Enjoy the remaining portion of the year. You’re conducting a useful job.

You’ve been great to me. Thank you! http://www.kayswell.com

Your articles are extremely helpful to me. May I ask for more information? http://www.kayswell.com

I’d like to find out more? I’d love to find out more details. http://www.hairstylesvip.com

You helped me a lot by posting this article and I love what I’m learning. http://www.hairstylesvip.com

Hi, of course this piece of writing is really nice and I have learned lot of things

from it regarding blogging. thanks. What does a vpn do https://tinyurl.com/2atd6fak

You helped me a lot by posting this article and I love what I’m learning. http://www.hairstylesvip.com

Your articles are extremely helpful to me. May I ask for more information? http://www.kayswell.com

You’ve the most impressive websites. http://www.kayswell.com

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me.

Can you write more about it? Your articles are always helpful to me. Thank you! http://www.kayswell.com

Thank you for writing this post! http://www.kayswell.com

Your articles are extremely helpful to me. May I ask for more information? http://www.kayswell.com

I appreciate, cause I found exactly what I was looking for. You’ve ended my four day long hunt! God Bless you man. Have a great day. Bye

Great content! Super high-quality! Keep it up! http://www.kayswell.com

Please provide me with more details on the topic http://www.kayswell.com

Valuable information. Lucky me I found your site by chance, and I am surprised why this

accident didn’t happened earlier! I bookmarked it.

I’d like to find out more? I’d love to find out more details. http://www.kayswell.com

Greetings from Carolina! I’m bored to death at work so I decided to check out your blog on my iphone

during lunch break. I really like the info you provide here

and can’t wait to take a look when I get home. I’m surprised at how fast your blog loaded

on my phone .. I’m not even using WIFI, just 3G ..

Anyways, great site!

Great content! Super high-quality! Keep it up! http://www.ifashionstyles.com

Great beat ! I would like to apprentice while you amend your web site, http://www.kayswell.com how could i subscribe for a blog site? The account helped me a acceptable deal. I had been a little bit acquainted of this your broadcast provided bright clear concept

I have seen loads of useful issues on your website about computer systems. However, I’ve got the viewpoint that lap tops are still less than powerful more than enough to be a sensible choice if you often do things that require many power, such as video croping and editing. But for website surfing, statement processing, and many other popular computer functions they are just great, provided you may not mind the screen size. Thank you for sharing your ideas.

I enjoyed reading your piece and it provided me with a lot of value. http://www.ifashionstyles.com

Thank you for writing this article. I appreciate the subject too. http://www.ifashionstyles.com

Of course, what a fantastic blog and informative posts, I definitely will bookmark your blog.All the Best!

Very interesting topic, appreciate it for putting up. “To have a right to do a thing is not at all the same as to be right in doing it.” by G. K. Chesterton.

Your place is valueble for me. Thanks!…

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me? https://www.binance.com/en-IN/register?ref=UM6SMJM3

After research a couple of of the weblog posts on your website now, and I truly like your way of blogging. I bookmarked it to my bookmark website list and will probably be checking back soon. Pls try my web site as effectively and let me know what you think.

Thanks for sharing. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good.

Excellent beat ! I would like to apprentice while

you amend your website, how could i subscribe for a blog web site?

The account helped me a acceptable deal. I had been a little bit

acquainted of this your broadcast provided bright clear idea https://tinyurl.com/yt83ggsk eharmony special coupon code

2025

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me?

I all the time used to study paragraph in news papers but now

as I am a user of web so from now I am using net for

content, thanks to web.

Here is my web blog – http://winkler-martin.de/messages/61849.html

Hi would you mind stating which blog platform you’re using? I’m looking to start my own blog in the near future but I’m having a difficult time selecting between BlogEngine/Wordpress/B2evolution and Drupal. The reason I ask is because your design seems different then most blogs and I’m looking for something unique. P.S Sorry for getting off-topic but I had to ask!

Thanks for sharing. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good.

I just couldn’t leave your website prior to suggesting that I really loved the usual information an individual provide for your visitors? Is gonna be back steadily to check out new posts.

This web site is really a walk-through for all of the info you wanted about this and didn’t know who to ask. Glimpse here, and you’ll definitely discover it.

There is visibly a bundle to realize about this. I think you made various nice points in features also.

Along with almost everything which appears to be developing within this particular subject material, many of your perspectives tend to be relatively exciting. Nonetheless, I beg your pardon, because I do not subscribe to your entire theory, all be it stimulating none the less. It would seem to us that your remarks are actually not entirely rationalized and in simple fact you are generally yourself not even thoroughly certain of your assertion. In any event I did appreciate looking at it.

Just want to say your article is as astounding. The clarity in your post is simply spectacular and i can assume you are an expert on this subject. Well with your permission let me to grab your RSS feed to keep up to date with forthcoming post. Thanks a million and please keep up the gratifying work.

It’s actually a cool and useful piece of info. I’m happy that you shared this helpful info with us. Please keep us informed like this. Thanks for sharing.

I was reading some of your posts on this site and I think this website is really instructive! Continue putting up.

I’ve learn some excellent stuff here. Certainly price bookmarking for revisiting. I wonder how a lot attempt you set to make this kind of excellent informative website.

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me? https://accounts.binance.info/pl/register?ref=UM6SMJM3

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me. https://accounts.binance.info/pl/register-person?ref=UM6SMJM3

It’s hard to find knowledgeable people on this topic, but you sound like you know what you’re talking about! Thanks

certainly like your website but you have to test the spelling on quite a few of your posts. Many of them are rife with spelling issues and I to find it very bothersome to inform the truth nevertheless I will definitely come back again.

I blog quite often and I seriously appreciate your information. This article has truly peaked my interest. I am going to take a note of your website and keep checking for new information about once a week. I opted in for your Feed as well.

Brasilia Sex Guide

I don’t think the title of your article matches the content lol. Just kidding, mainly because I had some doubts after reading the article. https://www.binance.com/register?ref=IXBIAFVY

13win33…okay, I’m always on the lookout for a new place. This one seems alright. Not the best, not the worst. Some decent promos, I think. Check out 13win33 maybe you’ll have better luck than I did.

I am not sure where you’re getting your information, but great topic. I needs to spend some time learning more or understanding more. Thanks for wonderful info I was looking for this info for my mission.

Kryptocasinos haben oder hatten in der Anfangszeit den Ruf, anonymes und unbeschränktes Glücksspiel zu ermöglichen. Mit dem

Token möchte Shuffle-Gründer Noah Dummet einerseits seine

Expertise in Sachen Krptowährungen ausspielen und andererseits die Herausbildung einer eigenen Community fördern. Wer spielen möchte, muss seinen Account zuerst mit einem Guthaben ausstatten.

Neben den Casinospielen steht Kunden überdies ein Sportsbook mit klassischem Sportwetten Angebot

zur Verfügung. Auf Shuffle.com wird Casinospielern alles geboten, was ihr Herz begehrt – angefangen bei

einer Fülle an modernen Spielautomaten, bis hin zu den Originals.

Unsere Priorität ist es, dir ein sicheres und unterhaltsames Umfeld zu bieten, in dem du dich voll und ganz auf dein Spiel konzentrieren kannst.

Bei Shuffle können Sie Casino-Spiele von den besten Anbietern der Branche spielen,

darunter Hacksaw Gaming, Pragmatic Play, NoLimit City, Push Gaming, Play’n Go, Relax Gaming, BGaming, Evolution und

mehr. Erleben Sie das ultimative Live-Casino-Erlebnis bei Shuffle, mit echten Dealern und in Echtzeit,

während Sie unterhaltsame Spielshows spielen oder

bei Blackjack und anderen Live-Dealer-Spielen gewinnen. Sie haben auch die Möglichkeit, die großen Gewinne mit nach Hause zu nehmen, indem Sie Jackpot-Slots spielen und einen festen oder progressiven Mega-Jackpot knacken. Die Spiele bei

Shuffle sind einfach und bequem von zu Hause aus zu spielen, einige

davon sind bereits aus landbasierten Casinos bekannt, wie Slots, Roulette, Blackjack, Baccarat und andere Tischspiele.

Bei Shuffle haben Sie Zugang zu Tausenden von verschiedenen Spielen, die Sie dank der Implementierung von Kryptowährungen in Sekundenschnelle

spielen können.

References:

https://online-spielhallen.de/vulkan-vegas-casino-promo-codes-ihr-leitfaden-zu-spannenden-boni/

Kostenlose professionelle Weiterbildungskurse speziell für Mitarbeiter von Online Casinos,

die sich auf die Erfahrungen aus der Branche stützen,

und die auf die Verbesserung der Spielerkenntnisse und auf einen fairen und verantwortungsvollen Umgang mit dem Glücksspiel abzielen. Durchsuchen Sie alle

von DaVincis Gold Casino angebotenen Boni, einschließlich jener

Bonusangebote, bei denen Sie keine Einzahlung vornehmen müssen, und durchstöbern Sie auch alle Willkommensboni, die Sie bei Ihrer

ersten Einzahlung erhalten werden. Wenn es Ihnen gelingen sollte, hoch zu gewinnen, und Sie Ihr Geld auf einmal

beheben möchten, so kann dies dann mehrere Monate oder Jahre dauern, bis Sie den gesamten Betrag ausbezahlt bekommen. Weitere Informationen zu allen Beschwerden und Schwachstellen finden Sie in dieser

Bewertung im Teil „Erklärungen zum Sicherheitsindex”. DaVincis Gold Casino hat eine gefälschte Glücksspiellizenz.

Der Erster Einzahlungsbonus von Da Vinci’S Gold Casino bietet deutschen Spielern einen unglaublichen Start. Der Da Vinci’S Gold Casino Willkommensbonus bietet im Vergleich zu anderen Casinos eine unkomplizierte

und attraktive Möglichkeit, das Spielerlebnis zu starten. Sie erhalten 75 Freispiele, die Sie sofort nutzen können. Cocoa Casino,

etabliert im Januar 2005, ist eine der Schwesterseiten von Da Vinci’S Gold Casino und bietet eine

Vielzahl von spannenden Boni, darunter einen Willkommensbonus

von 200% und bis zu 30% Cashback.

Das Angebot startet mit allen sämtlichen Tisch- und Kartenspielen.

Wenn Sie mit höheren Einsätzen spielen, wenden Sie sich bitte an den Support.

Ich zeige euch, wie es sich anfühlt, hier zu spielen. Diese beinhalten oft einen Einzahlungsbonus, Freispiele

oder Cashback-Optionen, die das Startkapital erheblich erhöhen können. Das

Casino stellt eine breite Auswahl an Slots, Tischspielen und Live-Dealer-Spielen bereit, die durch hohe Qualität überzeugen.

Nice blog! Is your theme custom made or did you download it from somewhere?

A design like yours with a few simple tweeks would really make my

blog stand out. Please let me know where you got your design. Bless you

vpn https://www.highlandguides.com

I got what you mean , thankyou for posting.Woh I am thankful to find this website through google. “Those who corrupt the public mind are just as evil as those who steal from the public.” by Theodor Wiesengrund Adorno.

Your point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you.

The High Roller befindet sich in unmittelbarer Nähe vom 5-Sterne-Caesars Palace Hotel & Casino Las Vegas und

ist unter anderem innerhalb von etwa 10 Gehminuten zu erreichen. Am südlichen Ende des

berühmten Strips gelegen, bietet… Hilton Grand Vacations

Club Elara Center Strip ist ein außergewöhnliches Ziel für Reisende, die das pulsierende Leben von Las Vegas hautnah

erleben möchten. Das Circa Resort & Casino – Adults Only in Las Vegas bietet ein einzigartiges Erlebnis

für Erwachsene, die inmitten des pulsierenden Lebens von Downtown entspannen möchten.

Das erschwingliche 2-Sterne-Days Inn By Wyndham Las Vegas Airport Near The Strip verfügt über 2 Casinos und liegt 2

km weit weg vom Mandalay Bay Resort and Casino.

Bali Hai Golfklub befindet sich circa 5 Kilometer von dem komfortable 2-Sterne-Highland Inn Las Vegas entfernt und ist einen Besuch wert.

Das 4-Sterne-Orleans Hotel And Casino Las Vegas bietet eine

großartige Lage in 2 km Entfernung von Wellness-Einrichtungen wie dem MGM Grand

Hotel und bietet allen Gästen ein Restaurant.

Das 4-Sterne-Jet Luxury At The Signature Condo Hotel Las Vegas mit einem beheizten Swimmingpool

liegt direkt neben dem Planet Hollywood Resort and Casino

und ist nur 12 Minuten zu Fuß vom The… Das Thunderbird Boutique Hotel Las Vegas beeindruckt die Gäste mit einem Swimmingpool und

liegt unter anderem im Viertel Downtown Las

Vegas – Fremont Street. Das 3-Sterne-Hotel Excalibur Las Vegas befindet sich weniger als 7 Minuten zu Fuß von der Bodies The

Exhibition entfernt und bietet seinen Gästen einen Gepäckraum und ein Restaurant.

References:

https://online-spielhallen.de/smokace-casino-cashback-ihr-weg-zu-mehr-spielguthaben/

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me? https://accounts.binance.info/id/register-person?ref=UM6SMJM3

Can you be more specific about the content of your article? After reading it, I still have some doubts. Hope you can help me. https://www.binance.info/register?ref=IHJUI7TF

This text is priceless. How can I find out more?

https://axisbd.com/decouvrez-atlas-tv-conseils-et-guide-iptv-2025/

We provide tools for setting personal limits, offer self-exclusion options, and

encourage players to take regular breaks. Additionally, the casino features a comprehensive FAQ section on their website, which addresses common questions and offers solutions to frequently encountered problems.

Players can contact customer support via live chat for immediate assistance, ensuring

quick and effective resolution of issues. Yes, Skycrown Casino

is well-known for its attractive bonuses and promotions.

The diverse game library ensures that there is something for every kind of player, from the casual gamer

to the high-stakes enthusiast.

Specialty titles such as keno, bingo, scratch cards, and video poker add further

depth, ensuring there’s something to suit every

Australian player’s style. Players will also find feature-rich slots with free

spins, multipliers, cascading reels, and Megaways mechanics.

Ongoing value comes from weekly reloads, cashback on weekend play and a rewarding VIP programme.

Clear policies explain how data is stored and protected, while customer support is trained to

help users manage their limits. Security at this platform is taken very seriously, with modern SSL encryption protecting every transaction and login attempt.

The site copies the real design to look trustworthy, but once you deposit, everything goes wrong — no

payouts, no real support, and fake bonus offers. I deposited thinking it was the real site, only

to realize later that support never replies, bonuses

don’t activate, and withdrawals sta… Some people claim that bonuses do not activate and that the platform freezes during gameplay,

leading to loss of funds.See more Bonus Buy slots are an exciting category where players can purchase in-game bonuses directly, unlocking special features instantly.

Crash games at Sky Crown Casino provide fast-paced, high-adrenaline gaming experiences.

References:

https://blackcoin.co/about-ripper-casino/

When a video is uploaded, it is checked against the database, and flags the video

as a copyright violation if a match is found.

The system, which was initially called “Video Identification” and later became known as Content ID,

creates an ID File for copyrighted audio and video material, and stores it in a database.

In April 2013, it was reported that Universal Music Group and YouTube have

a contractual agreement that prevents content blocked on YouTube by a request from UMG from being restored, even if the

uploader of the video files a DMCA counter-notice.

In April 2012, a court in Hamburg ruled that YouTube could be held responsible for

copyrighted material posted by its users. YouTube’s owner Google announced in November 2015

that they would help cover the legal cost

in select cases where they believe fair use defenses apply.

From 2007 to 2009 organizations including Viacom, Mediaset, and the English Premier League have filed lawsuits against YouTube, claiming that it has done too little

to prevent the uploading of copyrighted material.

YouTube Premium was originally announced on November 12, 2014, as “Music Key”, a

subscription music streaming service, and was intended to integrate with

and replace the existing Google Play Music “All Access” service.

It offers advertising-free streaming, access to original programming,

and background and offline video playback on mobile devices.

In 2014, YouTube announced that it was responsible for the creation of all

viral video trends, and revealed previews of upcoming trends, such as “Clocking”, “Kissing Dad”, and “Glub Glub Water Dance”.

In 2008, all links to videos on the main page were redirected to Rick Astley’s music video “Never Gonna Give You Up”,

a prank known as “rickrolling”. YouTube expanded the

removal of Russian content from its site to

include channels described as ‘pro-Russian’. Russia threatened to

ban YouTube after the platform deleted two German RT channels in September 2021.

References:

https://blackcoin.co/ax99-casino-australian-real-money-gaming-hub/

As you can see from our list, there are quite a few different types of casino platforms out there.

There is, of course, nothing really groundbreaking or weird about this.

While you might want to spend some time trying different alternatives, those with established tastes can simply filter games based on the studios that

they have grown to like. Nolimit City, in turn, prefers ultra-volatile games with crude humor

and dark overtones. Australia’s number one export is

Big Time Gaming, for instance, is known for its mega-popular Megaways games whose multipliers can sometimes grow to utterly ridiculous sizes.

Instead of sitting on your Bitcoin, Ethereum, Dogecoin, Ripple,

and Shiba Inu tokens, you could also take them

to a crypto casino in Australia.

Aussie Online casinos are known for their wide game selection, but not every site

has the same pokies and table games available.

To find a great casino, Australia online players should look for

a whole range of factors when deciding whether it’s right

for them. Use our reviews & rating guides to instantly compare EVERY Australian casino gaming site and find the best online casino for

you. Remember to use secure payment methods and practice responsible gambling to make the

most of your online casino journey. By following a few simple

steps, you can create an online casino account and start enjoying your favorite games.

Signing up at an Australian online casino is easy, designed to get you playing quickly.

References:

https://blackcoin.co/40_best-vip-online-casinos-for-high-rollers-in-2022_rewrite_1/

Afternoon showers. ESE winds shifting to SSW at 15 to

25 km/h. NNW winds shifting to E at 15 to 25

km/h. Skies clearing late.

Take control of your data. Chance of rain 50%.

NNW winds shifting to ENE at 15 to 25 km/h. Chance of rain 60%.

References:

https://blackcoin.co/casino-rsm-club-in-depth-review/

Yes, some online casinos in Australia for real money process and deliver withdrawals in 24

– 48 hours. We’ve examined the legality of safe online casinos in Australia from

three angles – what the law says, how it applies to you,

and how it can impact your gaming experience.

If you want to make the most of your gaming experience at AU online casinos, the worst thing you can do is chase losses.

Look for games with lower minimum bet requirements to get more

spins and rounds out of your current budget at the best Australian online casino.

Live dealer table games are designed to bridge the gap between land-based casinos and online gaming.

The best online casinos in Australia feature thousands of pokies in addition to blackjack, poker, baccarat, roulette, craps, specialties, and classic card games.

Many of the best online casinos in Australia feature no deposit bonus

codes. Top Aussie casinos often stand out because of welcome bonuses, reloads,

free spins and cashback that extend playtime. The best online casinos in Australia feature top-rated pokies, generous promotions, dedicated customer support, and compatibility for local payment methods.

Medium chance of showers in the north, slight chance elsewhere.

Winds southerly 15 to 25 km/h. Medium chance of

showers.

Mostly cloudy. Showers late at night. Chance of rain 40%.

Afternoon showers. NNW winds shifting to ENE at 15 to 25 km/h.

Skies clearing late.

References:

https://blackcoin.co/casumo-casino-review-rewards-slots-and-payments-how-is-customer-service/

gamble online with paypal

References:

https://jobsharmony.com

paypal casino usa

References:

cheongbong.com

online casino that accepts paypal

References:

https://wsurl.link/yfsgri

paypal casino canada

References:

https://lookingforjob.co/profile/lanbedard1205

gamble online with paypal

References:

https://iqschool.net/employer/best-online-casinos-australia-2025-find-top-aussie-casino/

online casinos that accept paypal

References:

https://vhembedirect.co.za/employer/online-casino-australia-top-real-money-casino-list/

After study a few of the blog posts on your website now, and I truly like your way of blogging. I bookmarked it to my bookmark website list and will be checking back soon. Pls check out my web site as well and let me know what you think.

There is noticeably a lot to identify about this. I believe you made certain good points in features also.

This is very interesting, You are a very skilled blogger. I’ve joined your feed and look forward to seeking more of your magnificent post. Also, I have shared your website in my social networks!

https://igruli.com.ua/5-pomylok-pry-vybori-bi-led-linz-yaki.html

As a Newbie, I am constantly searching online for articles that can aid me. Thank you

Just desire to say your article is as amazing. The clarity in your post is just great and i could assume you are an expert on this subject. Fine with your permission allow me to grab your RSS feed to keep updated with forthcoming post. Thanks a million and please carry on the gratifying work.